Franckie Alarcon: Sketching Sushi

Mouthfuls of raw fish are an integral part of Japanese cuisine and need no introduction. But how many people know just how many hours of hard work are required to put together these dishes which are devoured in a matter of seconds? And just how many people, from the fisherman to the Michelin-starred chef, work together to elevate fish flesh to the status of art?

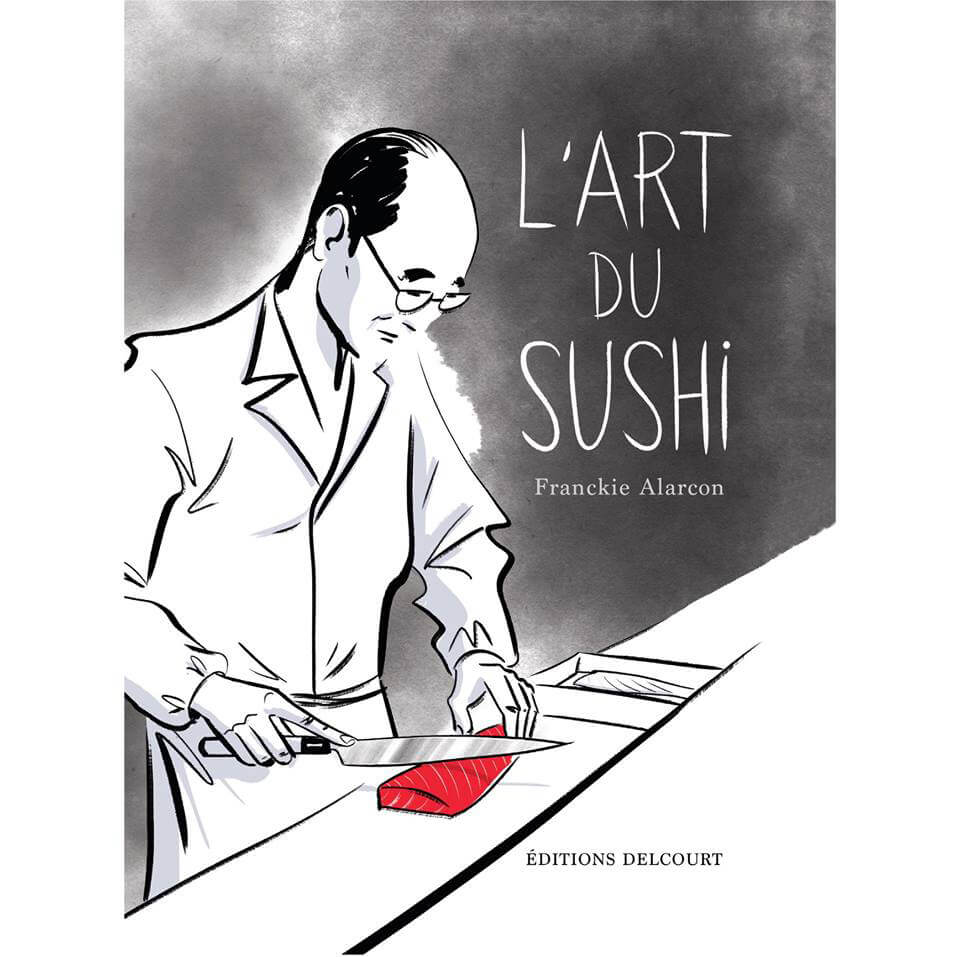

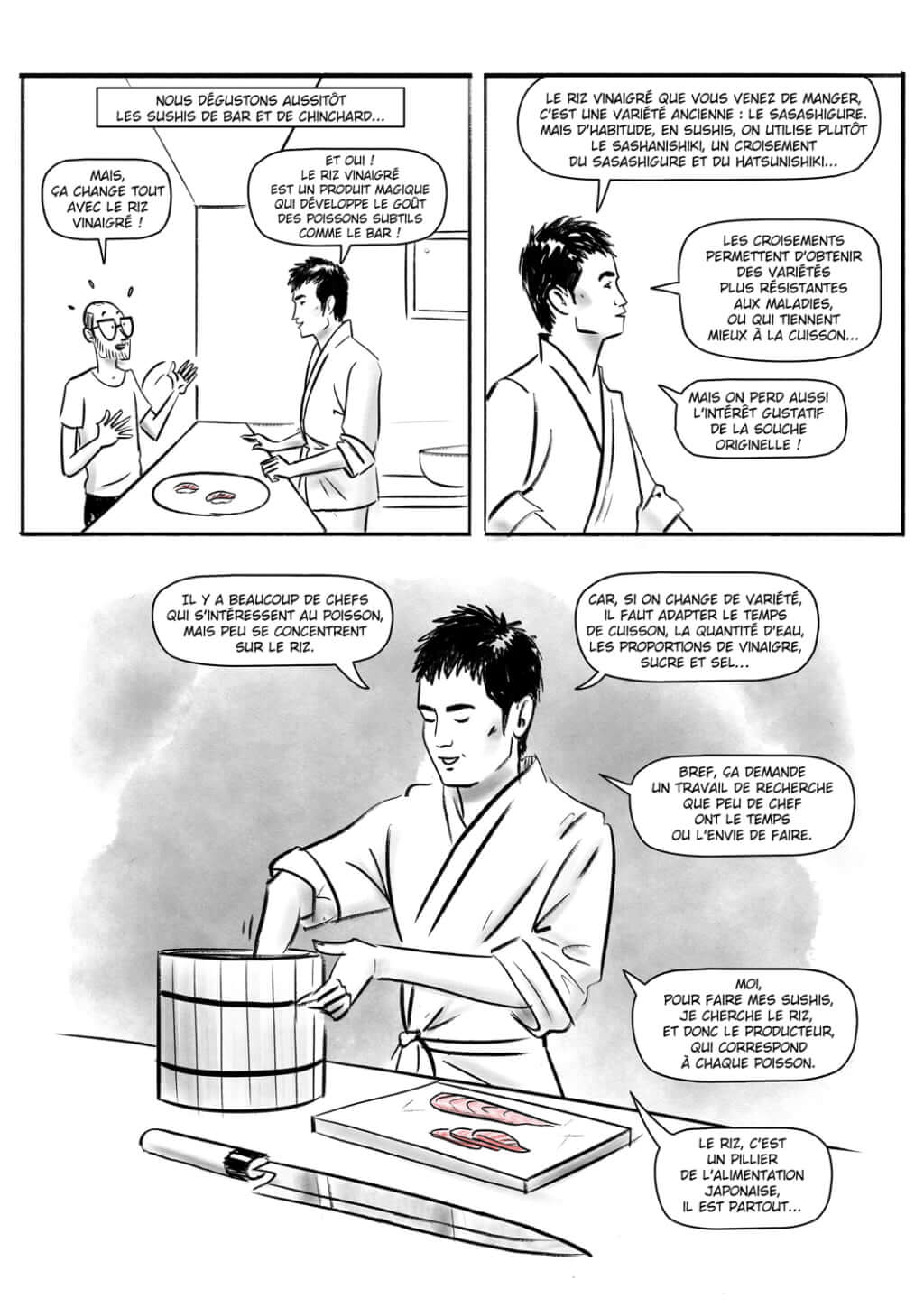

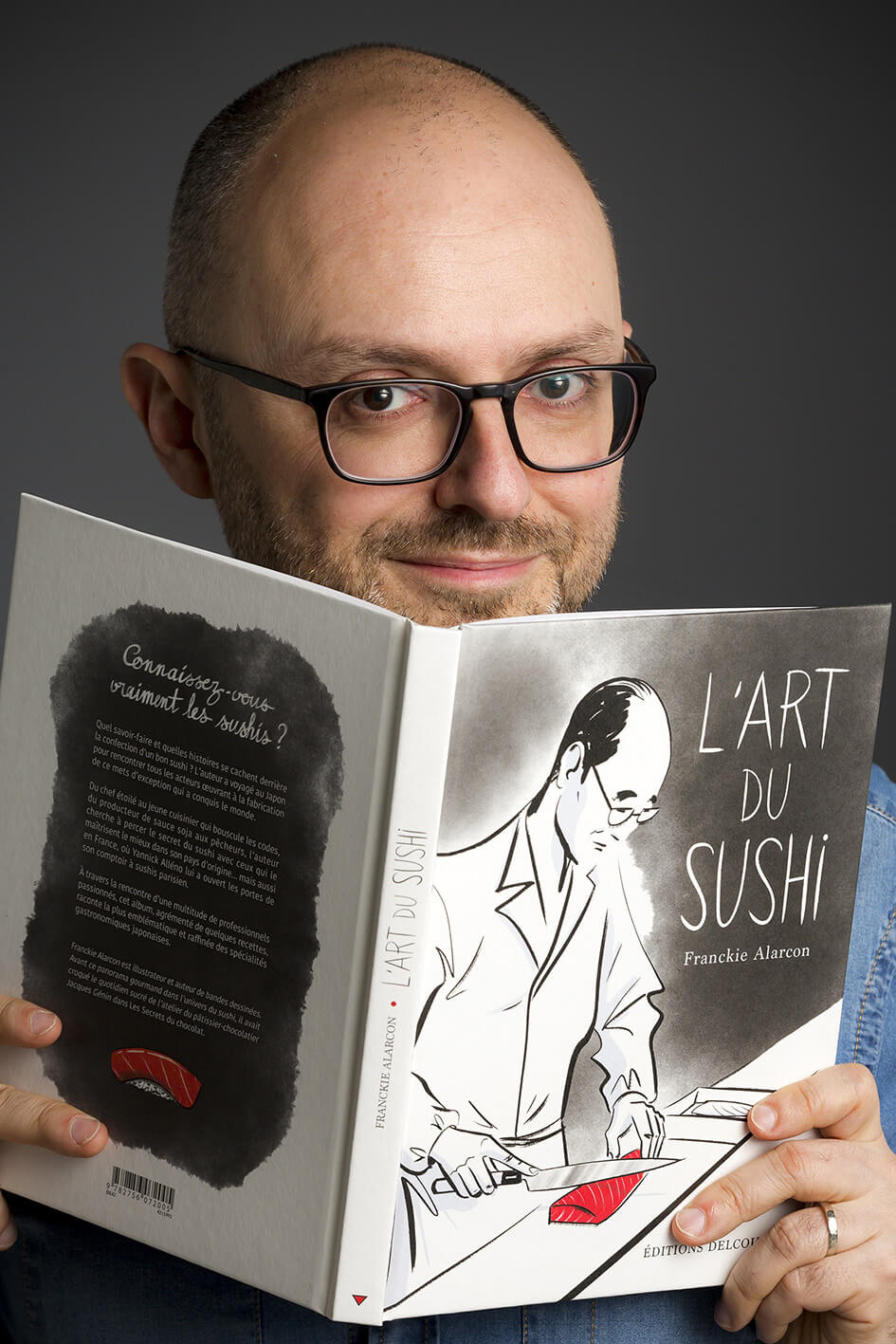

Franckie Alarcon seeks to answer these questions in L’Art du Sushi (The Art of Sushi), published by éditions Delcourt. It’s an illustrated story narrated in the first person which traces the journey of sushi from sea to plate. The foods are all characters in their own right and stand out against the black and white minimalism of the scenes thanks to their bright colours. The fish takes on a seductive quality and makes the mouth water.

‘I can recognise shellfish and sketch them from memory’, the artist explains. ‘But I wanted the drawings of the fish to be precise, so I took inspiration from photos taken on the spot’.

Franckie Alarcon discovered the joy of sushi when he arrived in Paris at the start of the 1990s. The Breton artist was accustomed to shellfish and, until then, had never imagined eating fish raw. Japanese cuisine aroused his curiosity and so he made his first trip to Japan, lasting over two weeks, in 2015, accompanied by his editor David Chauvel and their partners. Together, they aimed to understand why Japan is the land of sushi.

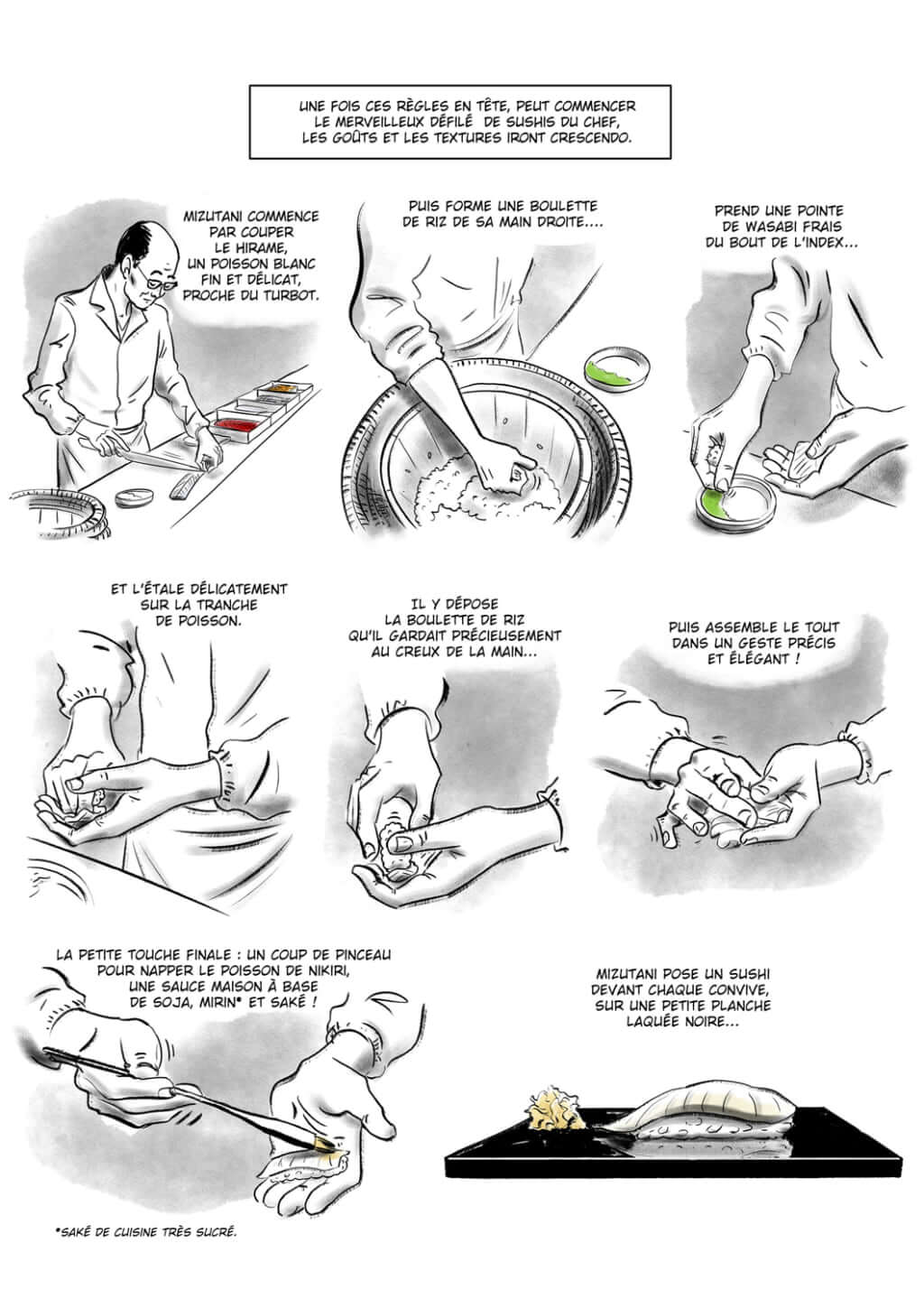

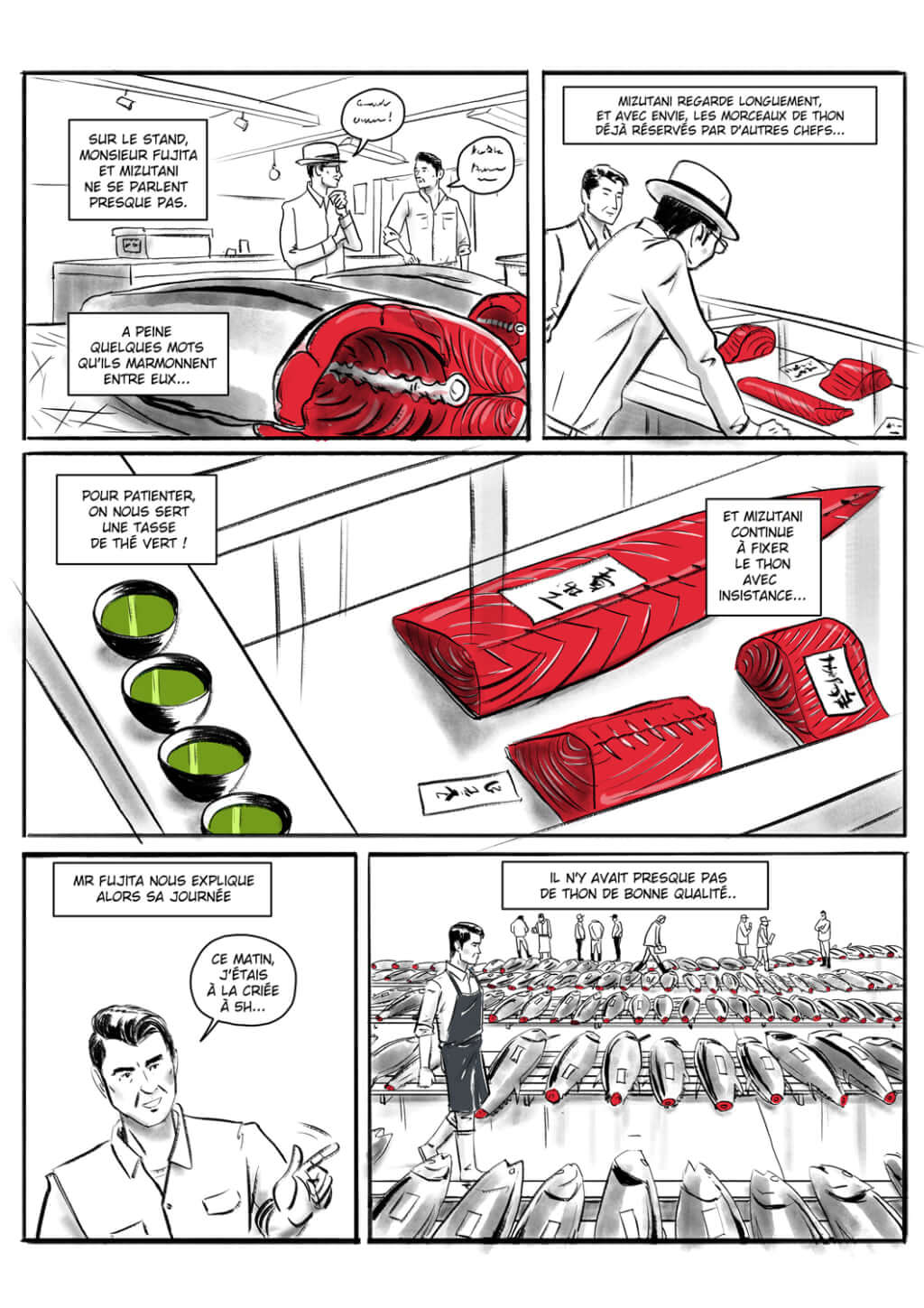

The first stop was Tsukiji fish market (which has since relocated to Toyosu) in the company of sushi master and holder of three Michelin stars, Hachiro Mizutani. Mizutani is not lacking in humour and tells of his surprise at seeing ‘very, very dead’ fish on market stalls during a visit to France. This exemplifies the difference in approach taken by the two countries towards seafood. Chef Mizutani prefers to select his fish while it’s still alive. He then leaves his supplier to prepare the fish according to a practice named ikejime which allows the fish to be killed but its freshness to be maintained at the same time. All of this is done so that Mizutani can control the ageing of the flesh in his restaurant depending on his desired flavours.

Franckie Alarcon was also struck by the lack of a smell of fish at Tsukiji, which he visited three times during his stay. This is another difference between Japanese and French markets such as Rungis. ‘We, French people, have a lot to learn about fish processing’, he reveals.

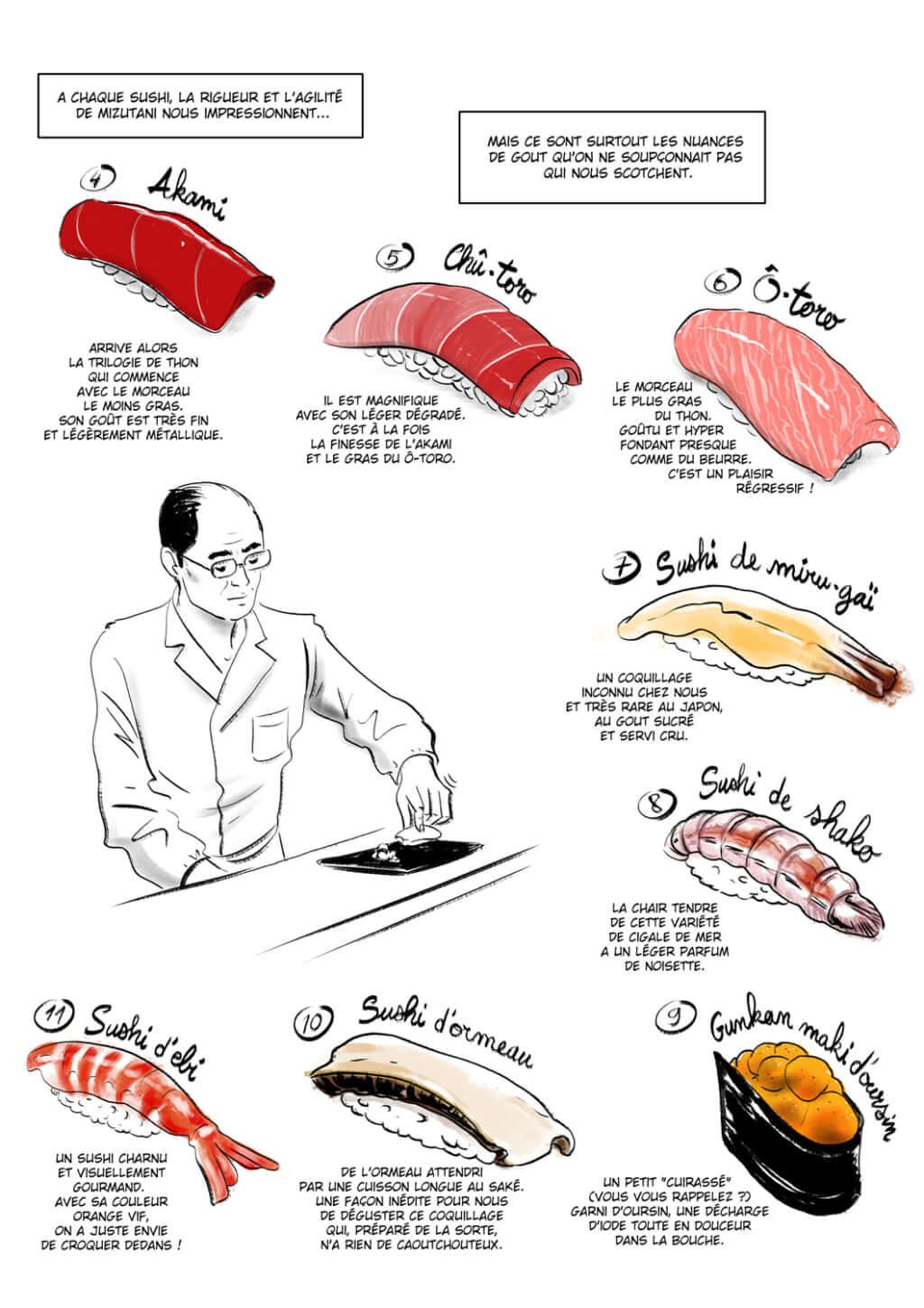

He also takes us with him on his journey to learn about the taste of sushi. The training required to become a traditional sushi master like Mizutani is long and difficult, and chefs generally only touch fish after three or four years of experience. Some chefs, however, like young Daisuke Okada, break from tradition. He uses types of fish rarely found in this kind of dish, serving up innovative and incongruous varieties of sushi in his restaurant, Sumeshiya, such as Mizutako sushi, made from giant octopus, and shark sushi.

‘I tasted the best and worst maki I’ve ever eaten in Japan’, declares Franckie Alarcon, thus proving that anything is possible in the land of sushi, from secret chef’s counters to sushi served on conveyor belts (kaiten-zushi).

Far from being restricted to simple mouthfuls of fish, L’Art du Sushi also examines the whole ceremony involved in eating sushi, from etiquette to the dishes used, through the story of a trip to a ceramicist. The introduction to different types of sake, and to those which go best with sushi, completes this comprehensive, pedagogical guide, which will be loved by sushi novices and regulars alike. Not forgetting the list of top sushi spots in France and recipes that can be found at the back of the book, allowing the reader to jump in at the deep end themselves.

TRENDING

-

Yakumo Saryo: A Culinary Voyage in Tokyo

Shinichiro Ogata makes objects from glass, ceramics and bronze but is also a fantastic cook. Have a taste of both his talents at restaurant Yakumo Saryo.

-

WA BI GIN : (An Old) Affair of Passion

The Japanese distillery Hombo Shuzo, first known for their shoshu, decided to launch itself into artisanal production of gin. Thus, WA BI GIN was born.

-

Gome Pit, the Pop-Up Bar in a Waste Treatment Facility

Japan never ceases to surprise. Gome Pit is a pop-up bar with an unobstructed view over a pit where tonnes of waste are piled up before being incinerated.

-

A Japanese Tea Room Perched Atop a Rooftop

The building, in keeping with the minimalist style of its creator, offers a splendid view of Vancouver Bay and the surrounding mountains.

-

Discover Japanese Gastronomy Through The Solitary Gourmet Manga

This illustrated black and white album follows its lead through various bars, celebrating the Japanese art of living.